#5 Settling in Singapore Series: Films

Share

Editor: Seol Hye Soo @hyssl.kr

It’s been nearly five months since I moved to Singapore. These days, I no longer feel nervous or awkward when arranging for home repairs or cleaning services, making secondhand trades, or using the condo gym.

Beyond managing day-to-day logistics, I’ve found comfort in continuing the habits and routines I had in Seoul—reshaped to fit this new environment.

One thing I’ve always loved is going to the movies. Back in Seoul, I often went to the Megabox across the street from my old office at COEX, or to smaller indie cinemas like Emu Cinema and Laika Cinema. Here in Singapore, I’ve become a regular at The Projectors, which I introduced in a previous article—and I even signed up for their annual membership.

It’s not just about the difference in venue. When I’m sitting in a dark theater, cut off from the outside world both visually and aurally, completely immersed in the images and sound projected on screen—it doesn’t matter whether I’m in Singapore or Korea. The experience transcends location.

And yet, at the same time, watching films as a foreigner has given me a fresh perspective. I’m still engaging in something I love, but through a slightly different lens.

Here are five films I watched during my first half-year settling into Singapore that have stayed with me.

Spoiler alert: If you’re planning to watch any of them, I’d recommend bookmarking this article and coming back after you’ve seen them.

.

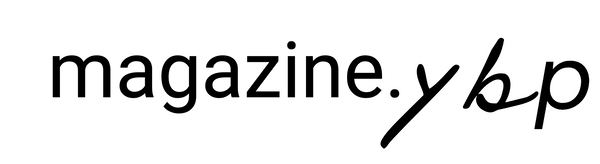

Photo credit: Perfect Days, Production: Wenders Images, Distribution: Anticipate Pictures

- Perfect Days

- Venue: The Projectors, Golden Mile Cinema

- Date: February 2024, one evening I can't remember the day of the week.

- During my unemployed period before joining my current company in Singapore, I took advantage of the luxury of going to the cinema for the first time and buying a same-day ticket. Although I saw the film without any prior knowledge, I consider it one of the most memorable films of the first half of this year. It depicts the recurring perfect days of a Tokyo public restroom cleaner, beautifully illustrating the beauty of maintaining a diligent routine. The day begins at dawn, when no one is awake. He waters his plants, carefully selects a cassette from his collection before heading to work, and cleans even the corners of his home that no one would otherwise see. He rides his bike to the bathhouse, and has dinner at his favorite restaurant. The morning begins again, and this cycle repeats throughout the film. Strangely, it doesn't feel boring. These seemingly monotonous days are filled with his favorite music, foods, and rituals, along with the chance encounters that bring variations. Komorebi (木漏れ日, こもれび), scenes of him observing the sunlight filtering through the leaves during lunchtime and capturing the moment with a film camera, evoke a sense of contentment and gratitude for life. A life of gratitude for the things we love, the things we take responsibility for, and the days we spend protecting them. Addressing the question, "What does a perfect day require?", director Wim Wenders speaks with a sophisticated yet simple tone, set in Tokyo, about values we often overlook, often overlooked by the peripherals that are often packaged and promoted as more important than the essentials. The soundtrack, comprised of pop songs from the 1960s and 1970s, including Lou Reed's "Perfect Day" and Nina Simone's "Feeling Good," which play during the Tokyo morning commute, further enhances the film's appeal.

Photo credit: Past Lives, Production: A24, Distribution: Shaw Organization

- Past Lives

- Venue: Sunset Cinema

- Date: 2024.05, Sunday afternoon

- Sunset Cinema is an annual event held in Singapore around April and May on the beach at Sentosa Island, offering a chance to enjoy a sunset and a movie. Sitting on the sand, wearing headsets, watching a movie felt different from watching it in a theater. The film that was showing was "Past Lives," which I had watched on a plane without much interest. I noticed scenes I hadn't noticed the first time I watched it (I've decided not to count plane-viewing movies as seen anymore). The first time I watched it, what stood out most was the relationship between Nora, Hae-sung, and her husband.

The second time, I began to see Nora’s lives. Somewhere deep inside her, the version of herself that once lived in Seoul had always remained. But to adapt to the unfamiliar, foreign world across the Pacific, she likely had to tuck that part away—into an invisible closet—and grow strong. The young Nora, crying alone in that closet, resurfaces in her dreams, sleep-talking in Korean. She reaches out for Hae-sung, someone who shares those lost years with her. In that final scene, when Nora embraces Hae-sung, perhaps she is opening that closet door. Perhaps she is gently taking out the young Nora, holding her close, and telling her it’s okay now—that there’s no need to cry anymore.

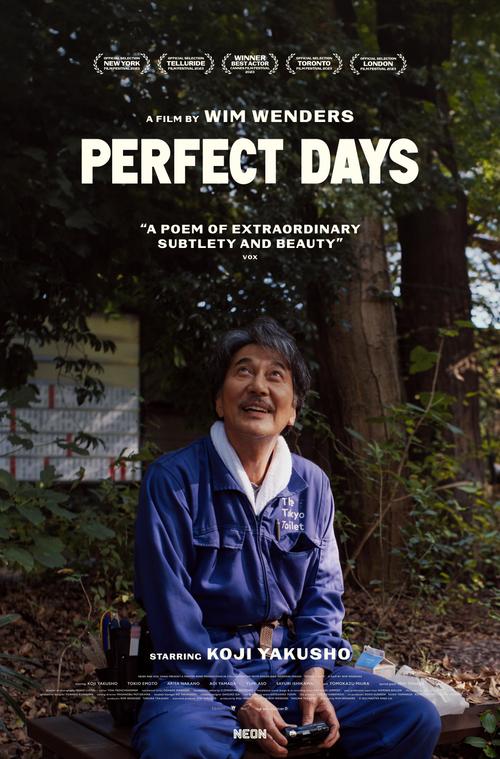

Photo credit: Challengers, produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, distributed by Warner Bros. Entertainment

- Challengers

- Venue: The projector, Cineleisure

- Date: June 2024

-

This is the latest film by Luca Guadagnino, best known for Call Me by Your Name.

Personally, I was deeply moved by his previous work, Bones and All, where he portrayed fragile yet quietly resilient characters through a love story steeped in gore. Also, I once had the chance to visit Crema, a small town in Italy where Guadagnino is from—and I could physically sense the aesthetic that runs through all of his films. So when news of his new release broke, I couldn’t look away.If I were to answer the question, “What makes a good film?” with “One that asks questions from many angles,”—this film might not exactly meet that standard. And yet, Guadagnino’s signature season—summer—paired with the world of tennis makes for a cinematic treat.

Players standing on the court, spectators watching, the ball flying back and forth between opponents—the tension builds through fast-paced cuts and shifting camera angles that mirror the rhythm of the match. Within that rhythm, the characters’ emotional states are portrayed with striking clarity.

The extreme close-ups, which seem to reveal every pore, were especially memorable. You can see the dilation of pupils, beads of sweat, the tightening of muscles. The fast, pulsing soundtrack amplifies the energy. Composed by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross—the same duo who won the Oscar for Soul and collaborated with Guadagnino on Bones and All—the score adds urgency and style.

If I had to choose just two tracks to recommend, they would be “Challenger” and “Brutalizer.” As the titles suggest, this film almost plays like an adrenaline-fueled music video starring Zendaya at full force.

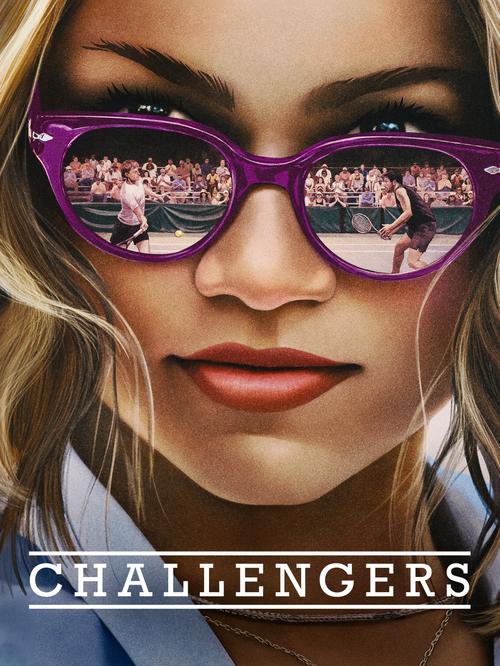

Photo credit: How to Make Millions before Grandma Dies, produced by GDH 559, distributed by Golden Village Pictures

- How To Make Millions Before Grandma Dies

- Venue: The Projector, Golden Mile Cinema

- Date: June 2024, a Wednesday evening filled with a hearty meal at the BBQ Box.

-

Here we have a grandson who makes you want to smack him upside the head—the kind who asks, “My grandmother is terminally ill. How do I win her over before she dies so I can inherit her fortune?”

The film is filled with the unconditional love of a grandmother who gives selflessly in her own way—to her clueless children and even more clueless grandchildren. While one of her grandsons slowly opens up and redeems himself in the face of her quiet devotion, there’s also a son who remains selfish to the very end—making this a deeply realistic portrayal of family.I’ve always disliked overly sentimental films, the kind that try too hard to make you cry. But somehow, this one brought back memories of The Way Home, a film I watched as a child about a young boy and his grandmother (likely because of the shared theme). Back then, I was younger than Sang-woo, the 7-year-old protagonist. Now, I find myself older than the college-aged grandson “M” in this story. That realization hit me like a wave: the kind of love you receive for decades—unchanging like vapor in the air—eventually gathers and falls like snow, heavy and silent, until it lands in your chest and breaks you open. By the end of the film, I couldn’t hold back the tears. When the credits rolled, most of the audience—regardless of background—remained seated in stillness, staring blankly at the screen. Perhaps we were all feeling the weight of love in our own way.

This film is currently the highest-grossing movie of the year in Thailand, and as a foreign viewer, I also appreciated the warmth of its visual palette. Through it, I was able to quietly glimpse Thai homes, neighborhoods, funerals, temples—everyday landscapes that reflect the country’s life and rhythms.

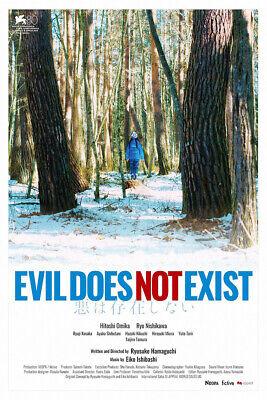

Photo credit: Evil Deos Not Exist, produced by Incline, distributed by Anticipate Pictures

- Evil Does Not Exist

- Venue: The projector, Cineleisure

- Date: July 2024

-

This is the latest film by Ryusuke Hamaguchi, director of Drive My Car. What immediately stood out to me was its running time—under two hours, a sharp contrast to the three-hour runtime of Drive My Car. (In fact, the film wasn’t originally intended to be a feature. It began as a live performance video project for music director Eiko Ishibashi, and later evolved into a film.)

The film begins by showing its title—one word at a time.

That alone invites you to sit with its meaning throughout the entire runtime. Set in a small rural village in Japan during winter, the landscape is almost entirely grayscale. Except for the last ten minutes, the film moves gently and quietly, allowing your attention to settle on the smallest of details: a single line of dialogue, a blue beanie, an orange puffer jacket, chopped firewood, fresh wasabi, the body of a deer.There are three main presences in the film: the villagers who live with deep gratitude toward nature; the Tokyo employees trying to commercialize the area by building a glamping site; and the forest and deer, which symbolize nature itself. The camera weaves between them with an inscrutable rhythm, demanding careful attention. The differences in perspective between these three parties give rise to harm—not from malice, but from misunderstanding. And that makes it all the more tragic.

The film ends with an explosion of conflict between nature and humanity—two worlds that seem incapable of coexistence.

It leaves you without a clear conclusion, but instead with a ripple of questions: What is good or evil? Conflict or coexistence? Human versus nature? Themes that may appear binary at first gradually reveal their layered complexities.In an interview with Cine21, music director Eiko Ishibashi said, “The role of film music is to help the audience think. Music shouldn’t define, impose, or steer the viewer’s emotions.” That philosophy applies not just to the music—but to the entire film.

If you're in search of thought-provoking seeds that branch out in unexpected directions, this film offers the kind of quiet clues that reward slow, reflective viewing.